It's been 12 years...

Premium update #14

…since Apple released the first iPad, Instagram was launched, and the North Atlantic Oscillation was as negative as it will be this December. Do you remember what you were up to 12 years ago? Clearly, a lot can happen and change.

But this is a weather blog, not a tech blog, so I’ll be focusing on the last point because it can give us clues as to what the weather will do through January 🔮

Join me on a hunt through the weather history books 📚

The North Atlantic Oscillation, or NAO for short, describes differences in air pressure between Greenland and Iceland in the North Atlantic Ocean and the Azores in the Central Atlantic Ocean.

Why should you care? Because weather happening in far off places can impact our weather!

The positive phase of the NAO involves low pressure and stormy weather up near Iceland and Greenland with high pressure and more settled conditions near the U.S. East Coast, including the Hudson Valley.

The negative phase is the opposite, with high pressure dominating toward Greenland and low pressure closer to us. This increases the chance for cold air and storms. The jet stream dips down over the eastern U.S. in order to compensate for the Greenland high pressure zone.

❄️ Fans of snow have been salivating this past week as forecasts became clearer that a major negative NAO episode will kick off next week and potentially last into January.

It will be the first major negative NAO episode in 12 years (since 2010) and looks to be among the 12 strongest episodes during the month of December since the year 1950.

These days, I find myself doing as much meteorology as data science. In order to be effective, I need to be able to analyze what happened in the other 11 NAO episodes and communicate it back to you in an interesting and informative way.

So that’s exactly what I plan to do!

First, I retrieved the NAO data that NOAA makes freely available online (yay!), all the way back to 1950.

Next, I open up a terminal shell on my mac where I tell my computer to launch Python, a coding language.

Shortly thereafter, I’m writing Python code in a virtual notebook. I call up the spreadsheet that has the NAO data — all 26626 rows!

Here’s what it looks like…

Next, I strip the data back and retain what I need. In this case, I only want data from the month of December…

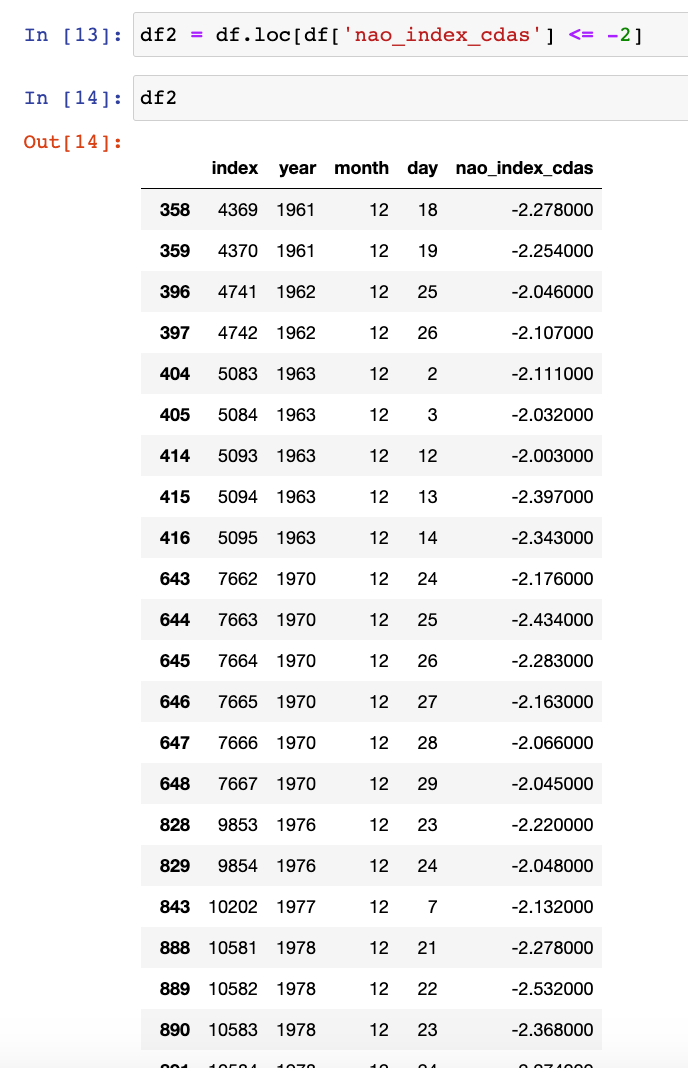

…and times when the NAO was strongly negative (≤ -2)…

That leaves me with 11 Decembers since 1950 when the NAO was strongly negative: 1961, 1962, 1963, 1970, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1997, 2008, 2009, and 2010.

I then plot all 2232 December NAO data points from 1950 - 2021 and highlight the years of interest (in red) — the major negative episodes.

Now that I have the information I wanted from this dataset, I need to go elsewhere to find historical weather data.

My (virtual) journey takes me to Europe, where the European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) hosts the most advanced simulation of historical weather conditions (called a reanalysis).

I download historical temperatures, snowfall, and atmospheric heights for the Decembers in the list. What I’d like to understand is how unusual those Decembers were, so I grab 30 years worth of additional historical December data to use as a reference point (called a long-term normal).

First, I assess atmospheric heights. This provides a big picture overview of the weather pattern across the Northern Hemisphere during the historical NAO episodes.

The big blob of red (higher atmospheric heights) over Greenland sticks out like a sore thumb! It implies warmer temperatures and more settled weather there.

The strip of blue (lower atmospheric heights) extending from the U.S. to Europe indicates a zone of colder, stormier conditions.

🥶 Let’s move on to temperatures.

Colder than average temperatures (🔵) had a tendency to infiltrate the U.S. during past NAO Decembers — in fact, colder than average temperatures covered most places in the Northern Hemisphere EXCEPT Greenland.

BUT, it is worth pointing out that we live in a warmer climate now than in the past. The temperatures that occurred during these historic episodes ≠ what will happen in 2022-23, but the general pattern will probably still ring true.

❄️ Finally, a look at snowfall.

In this map, blue (orange) colors indicate above (below) normal snowfall.

Much of the U.S. East Coast is covered in blue, including the Hudson Valley! ☃️

General patterns are great, but what exactly happened in the Hudson Valley during these Decembers and the following January? I have the data for that too!

We’re interested in January because the NAO pattern that developed during December tended to persist or repeat during the subsequent January.

As a premium subscriber, this is the type of deeper-level analysis that you get to see.

A continuous record of snowfall in the mid-Hudson Valley is a bit hard to come by, so here I aggregate data from Walden, Newburgh/Stewart, and Poughkeepsie.

What does this tell us?

In past NAO Decembers, the minimum snowfall was 8 inches, the maximum snowfall was 26 inches, and the interquartile range was 10-15 inches

In past NAO Januaries, the minimum snowfall was 3 inches, the maximum snowfall was 30 inches, and the interquartile range was 6-21 inches

The typical total snowfall range during December-January in past NAO events was 20-33 inches 👀

So there you have it! If history is to be a useful guide, the region should have received somewhere between 20-33 inches by February 1st, 2023. I’ll set a reminder to look back at this post in about 2 months 🙂

While this pattern does not guarantee a blizzard, it does elevate the odds for cold and snow 🌨️

In fact, NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center has outlined a “slight risk of heavy snow” over the period December 10th-16th.

🎄 For those hoping for a white Christmas, your chances are a little higher this year thanks to your newest friend, the negative NAO.

Very cool info

It’s simply fascinating that straight up numbers (historical data) can end up painting such meaningful illustrations and tell an such interesting story!