😎 A record tying temperature of 66 degrees on Wednesday, which is the average high in late April, might have you thinking that spring arrived early.

While there probably will be some more wintry weather before we officially farewell the season, the clock is ticking ⏳

Meteorological spring, March 1st, is just 11 days away — remember, meteorological seasons start a little earlier than astronomical ones. In the case of spring, it’s March 1st vs March 20th. Why the difference? Well, quite simply, it makes for easier record-keeping and combines the months with the most similar temperatures.

Spring is a time of change. The jet streams weaken as the temperature difference between the North Pole and the equator slackens, thanks to increasing amounts of solar radiation in the Northern Hemisphere ☀️

This sets into motion all sorts of things: the baseball season, bird migration, blooming flowers, and your favorite (not really) pollen 😷

Earlier this week, a big dump of data from international climate centers offered a glimpse at what next season may bring to the Hudson Valley.

Will winter arrive late, summer arrive early, or can we expect a “normal” spring?

I’ve sifted through the data, created some images, and I’m ready to tell its story…

Parts of this post were originally published in a premium post in September. I thought it was decent enough to republish ☺️

Some people look forward to Thanksgiving, Christmas, or a birthday, but for climate scientists, the 14th of every month is a holiday 🎁

Since late 2019, it has marked the day on which a coordinated “data dump” from the world’s top meteorological centers occurs.

This data provides insights on what the weather might be like — not over the next few days, but over the next six months.

It’s up to meteorologists to tell its story 📖

At 5:00 am on the 14th of February, my computer roared to life. Not because I was rising early, but because a “cron job” was triggered, an internal reminder that’s used to instruct a computer to perform a task at a certain time — in other words, a computer’s alarm clock.

By 5:05 am, my computer’s fan was audible, as it was feverishly sifting through freshly downloaded data from the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, France, Canada, the U.S., and Japan, beamed to my little laptop at the bottom of the Earth in New Zealand.

My Python scripts were busy turning the data, encoded in a special meteorological file type called “.grib”, into pictures that you or I can understand.

A picture in this case is the last link in a long chain that can start with something as simple as a sea temperature observation from a boat in New York Harbor.

Thousands of observations are used to construct a snapshot of the current state of the climate before sophisticated mathematical computer models run simulations of the future climate.

Each simulation is called an “ensemble member”. Each ensemble member is like an opinion. When the members have a similar opinion of the future state of the climate, forecast confidence is higher.

The “opinion” of each of the international centers is combined to create a super ensemble. Individually, the ensemble members make noise, but together, they make music.

The wisdom of the crowd is almost always more powerful than the wisdom of one.

By 5:20 am, colorful images were populating in different folders, one called temperature, another called snow, and several others with names that only weather nerds would understand.

The output of these climate models is typically assessed as an anomaly or a difference from average. It allows someone to clearly see what parts of the world are most likely to be warmer 🔴 or colder 🔵 than average and wetter 🟢 or drier 🟤 than normal.

Useful predictions are possible out to about 3 to 6 months, but skill declines as the influence of the initial oceanic and atmospheric conditions that are fed into the model wane.

At any rate, it’s time to do a little crystal ball gazing 🔮

Upper atmosphere

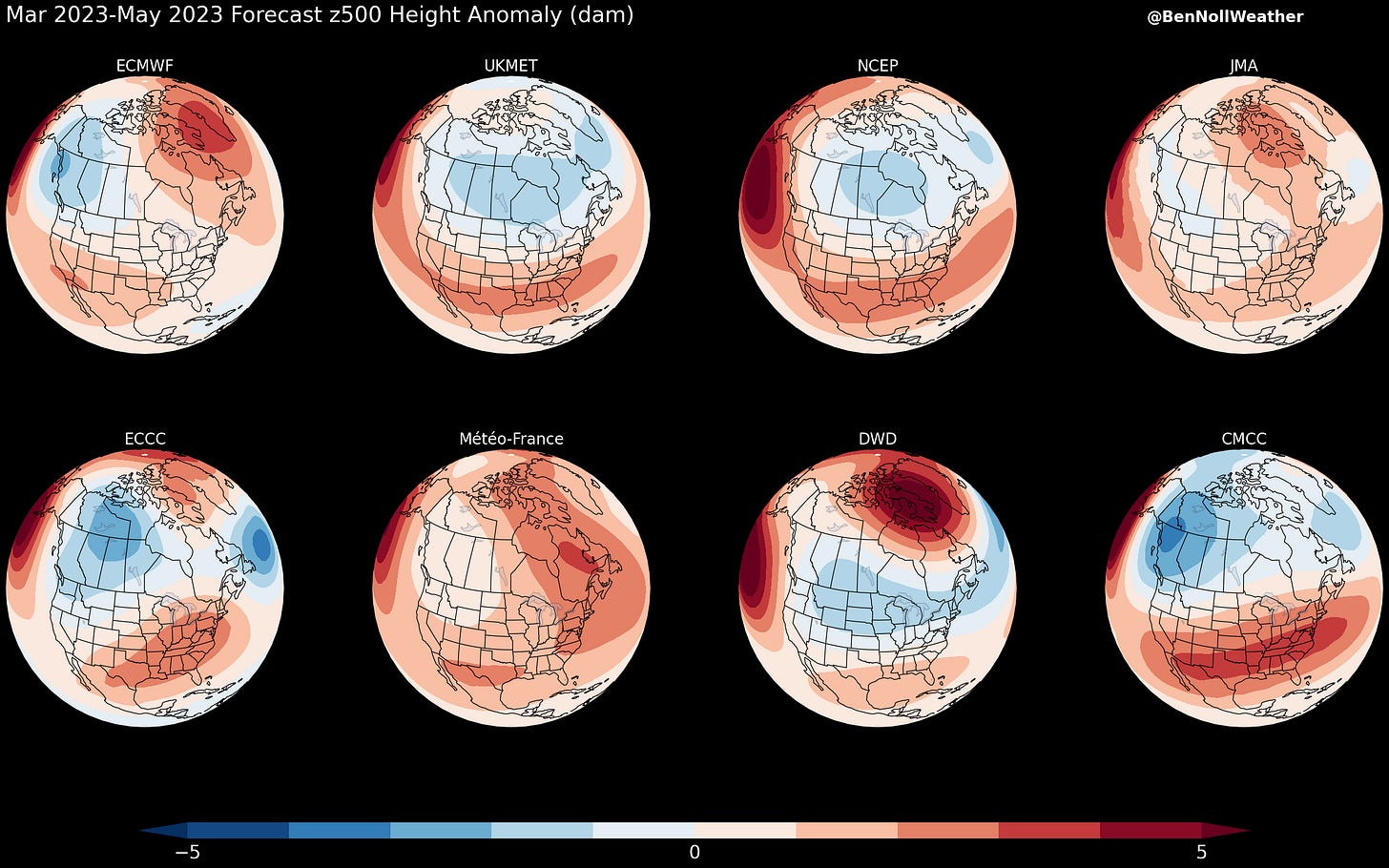

Blobs of red and blue, what do they mean? Lava from a volcanic eruption 🌋 meeting the icy abyss of the polar bears’ 🐻❄️ north? Not quite.

The long-range forecasting funnel starts wide. We want to answer the question: what does the broad circulation pattern look like? In other words, where is high and low pressure forecast to be?

The map below takes us to 500 hectopascals, some 20,000 feet above Earth’s surface. Things here, above even the tallest mountains in the continental USA, are a little less chaotic than at the ground. That means the models tend to be a little more accurate.

Red colors (🔴) indicate higher atmospheric heights, which generally implies more settled, warmer weather. Blue shades (🔵) indicate lower atmospheric heights and signal unsettled, cooler weather.

Opinions from 8 climate models are shown. Most of them signal a ridge of high pressure somewhere near the U.S. East Coast, which generally isn’t an ingredient in the recipe for a chilly spring in our part of the country.

While a wall-to-wall cool spring doesn’t look particularly likely, there is one particular factor that could throw a wrench into things 🔧

A handful of models show an area of high pressure near Greenland, which is an effective way of displacing cold, Canadian air southward into the United States.

I mentioned this in my post from last week — how something called a sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) event could have colder and snowier implications on our March weather patterns. The impacts of an SSW can linger for up to a month or two, which means that April’s outlook could be affected at some level — exactly how much remains to be seen.

We don’t live 20,000 feet above Earth’s surface, so we also look at…

Temperature

The weather maps are always red these days. This isn’t by design. It’s Mother Nature’s way of saying she has a fever 🤒

The average temperature is rising, which means that there will be fewer cold temperature extremes with time — we’ve experienced that first hand this winter. And, if you can believe it, winter 2022-23 will be considered a cold winter in 20-30 years time! Things are changing quickly.

Considering March-May as a whole, temperatures are predicted to be only slightly above average in the Hudson Valley.

Colder than average temperatures, denoted by blue coloring, will occasionally bleed southward into the northern tier of states.

When I see a map like this, my initial reaction is to not expect a really warm spring or an early arrival of summer in New York, especially in the context of the SSW.

Precipitation

The data certainly isn’t bashful when it comes to precipitation this spring. The maps are as green (🟢) as a Christmas tree, signaling above normal moisture.

It looks like low pressure systems will cut toward the region from the west with some regularity. Given the temperature outlook, this could certainly open the door to some spring snow!

Any snow that does fall, however, probably won’t stick around, as outlier, cold days will likely be surrounded by milder ones.

Also worth noting is the deep green seen lurking off the East Coast, which could be the model sniffing out coastal storms (nor’easters). We’ve lacked these so far this winter but it would seem weirdly fitting to have them start showing up in spring 🙃

Snowfall

Climate models also predict snowfall. Unlike air pressure, temperature, and precipitation, it isn’t a field that is routinely assessed by climate scientists.

I’ve been tracking its performance over the last few winters. It’s predicted lower than normal snowfall the last 4 winters and was accurate in 3 of the 4.

It continues this theme in March (🔴 - below normal snowfall) but boy, those dark greens (🟢 - above normal snowfall) aren’t very far away!

I think it’s suggesting that we’ll have some chances during March but we might just find ourselves near the dreaded rain / snow line! ❄️

tl;dr It’s looking like we’ll have a spring with those typical roller coaster-like swings, but a record warm or cold season seems unlikely. There’s an elevation in the chances for snow and chilly spells in March and maybe April. Any cold air will probably be fleeting and followed up by milder conditions. Be ready for anything and everything!

As a premium subscriber (and fellow weather nerd 🤓) you are the first to see this information. It’s pretty custom stuff, providing whispers of the weather that we may experience in the seasons to come.

Now, we wait — until my computer roars to life again at the crack of dawn on March 14th ⏳

Thanks, Ben. I was watching videos of my kids in some of the blizzards from the '90s and wondering if my grandkids will ever have the same experience. I really appreciate your big picture take on climate change.

Thank you, Ben. You make weather discussion so academically understandable. I quote you all the time. My friends even ask, “What does Ben say for tomorrow?”